#RamadanSeries – Masjid E Zubaida

Published each Friday during the Holy Month of Ramadan, the #RamadanSeries looks at contemporary mosques around the world.

Season 4 – Episode 1: Masjid E Zubaida in Raichur, India.

A Masjid is a “place of prostration”, which means ‘kneeling’. Islamic architecture is not regional. Over the years, most of the pre-Islamic vernacular forms and characteristics have gradually become an eclectic mix of the elements and characteristics of areas where Islam had spread.

Unlike historical monumental mosques, contemporary mosques are designed to exhibit these transformed forms establishing a unique identity of their own; Masjid-e-Zubaida by Neogenesis+Studio0261 being one such example.

The design was conceived with a primary notion that a religious space should be such that it helps meditate; cleanses emotionally and spiritually to be in a direct connection with God. The building was articulated by identifying essential elements of a mosque after analysing the function and symbolic values of each and focusing precisely on the essentials rather than mere aesthetics and grandeur.

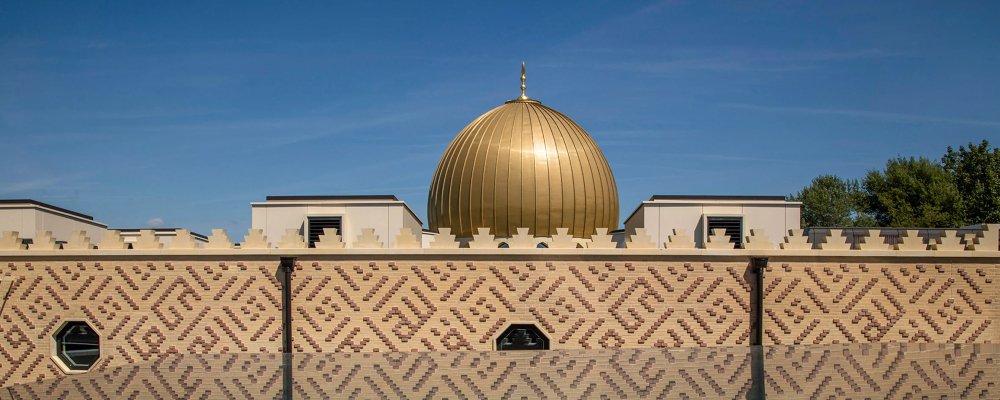

With this in view, the mosque (750 sqm) has been designed to combine the fundamental basics in terms of spaces and elements with a high functional value such as Ibadat khana, Minbar, Mihrab, and the Minaret with a sober and contemporary architecture. The minaret acts as a visual mark for the mosque. Not merely functional in nature, it also serves as a powerful visual reminder of the presence of Allah. The aesthetic of the mosque is based on the notion that materiality has to be sustainable and locally sourced; Compressed Stabilised Earth Blocks (CSEB) made out of the excavated soil were planned to be used for that purpose.

Regrettably, the blocks failed in compression and the architects, later, had to switch to boiler bricks that were made in the client’s factory. The presence of Madrassa in the basement of the mosque aids multiplicity. While not a ritual requirement like the Mihrab, a dome more often used to be a structural requirement to carry larger spans, which also turned into a symbolic representation of the vault of heaven. But, with advancing technologies and construction techniques, the need for domes for achieving larger spans has faded with time. Hence, a clean form was chosen as the main mass with a flat roof under which the Ibadat khana would rest; to adhere to simplicity and individualism.

Exposed brick jali makes up most of the facade allowing sunlight to penetrate inside that making the whole space divine and creating a ‘sense of awe’. The louvered glass, incorporated into the doors and facades, aids light and ventilation. The openings on the upper side of the Ibadat Khana further enhance the environment and additionally light up the space.

The Qibla wall (the holiest section of the mosque) has been kept plain and serene to turn off one’s attention from the outside environment. Sunlight from the skylight above gradually washes the wall as a reminder that ‘Allah’ is the light of the heaven above. The flooring, too, has been kept seamless to reduce the worshipper’s distraction and facilitate the required ‘khusyuk’ (concentration) for worship. The design develops a new language of the mosque, that is much more transformed, simple but unique, and merges with modern-day needs.

Pictures by The Fishy Project