‘Beirut. Eras of Design’ Exhibition

Despite all possible challenges, Lebanon’s design scene has flourished with a diverse palette of talents. ‘Beirut – Eras of Design’ exhibition portraits the dynamic evolution and growth from 1950s.

For this journey through time at the Centre of Innovation and Design, Le Grand-Hornu, Belgium, curator Marco Costantini (Mudac) focused on design as a key driver of Lebanon’s development and asked Ghaith&Jad to create a scenography around three main parts.

Beirut. Eras of Design will try to analyse this specific context, in which economic and architectural reconstruction, social awareness, and international development all come into play. Design encapsulates the country’s very desire to take control of its own destiny and image by proposing objects and forms that reflect a myriad of heritages but are also deeply rooted in a complex reality.

The aim is to showcase the dynamic evolution and growth of design in Lebanon, Beirut. Eras of Design features three sections.

Part 1: The History of Lebanese Design

From its liberation from the Ottoman yoke in 1918, its independence in 1943, its civil war (1975 to 1990), and more recently the two explosions in Beirut’s port on 4 August 2020, Lebanon is the culmination of a complex political situation. Producing something in the country today is an act of solidarity and fighting spirit. It is about helping a whole ecosystem of craftsmen work, maintaining an intangible heritage, a heritage of savoir-faire, and demonstrating to the political classes that, despite the obstacles, some Lebanese people want to stay in the country.

Works of students of the American University (AUB) and Académie libanaise des Beaux-Arts (Alba) of Beirut have been commissioned especially for this exhibition and well as a sound installation by Christophe Fellay will give a hearing dimension to the show.

Under the French Mandate (1918-1943), Beirut restructured itself according to the Western model and thus distinguished itself from most other cities in the Levant. Despite the considerable development of its suburbs - due to significant population growth - only the city centre benefited from all of this work. None of the proposed urban development plans (Danger and Michel Écochard) took into account the pre-existing urban forms, and work began as if on a blank slate, a sign of the denial of identity and the victory of colonial urban planning.

But it was between 1945 and 1975 - the era of the First Lebanese Republic - that design would really make its mark on the scene in Lebanon.

The exhibition begins by putting contemporary creativity into historical perspective, from the beginning of the 20th century to the early 2000s.

Amongst the protagonists or landmarks featured:

César Debbas: founder of Le Grand Magasin d’Électricité (1910), opened Lebanon’s first chandelier workshop in 1934.

The Saint-George Hotel: designed by French designers Poirrier, Lotte and Bordes, the practical work was overseen by Lebanese engineer and architect Antoine Tabet. Its opening in 1932 made it the city’s first luxury hotel. The hotel was burned down on 10 December 1975.

Jean Royère: the Parisian designer opened his architecture and design office in Beirut in 1947 in association with the Lebanese architect Nadj Majdalani. The role of this distinguished figure in Parisian interior design will be illustrated by a large number of documents.

Khalil Khoury: In 1958, the architect founded a modern architecture office with his brother Georges, where the focus was on exposed concrete. It is with Interdesign that Khalil Khoury would devote himself to design. The pieces designed there (usually made of wood, metal and leather) were exported mainly to Arab countries, but also to Europe.

Francesco and Aldo Piccaluga: They worked on a number of projects for banks, as well as a hotel (the Alcazar, 1960), and collaborated with Interdesign on furniture.

Jack Matossian and Maison Fontana introduced European tastes to the Lebanese middle classes with reproductions made in Lebanon. This was a response to the city becoming more international and the rise of hotels and cabarets in the 1950s. Fontana would close its doors in 2000, five years after Matossian’s death.

Sami El Khazen: is best known for creating the chandelier for the Lebanese pavilion at the World’s Fair in New York in 1964-1965.

Michel Harmouche: in 1951 he opened his architecture office in the old souks and later on two shops: ‘Perspectives’ with a wide range of lighting, furniture, fabrics and other design objects while ‘Retrospectives’ specialises in selling antiques.

Serge Sassouni: particularly enjoyed “embedding” elements of traditional architecture in his buildings. He then moved to the United States and was commissioned to design a number of restaurants and large hotels.

Pierre el-Khoury: built a number of significant buildings for the Lebanese government, including in particular the Roumieh prison in 1960, as well as buildings for Beirut airport. Working with Khalil Khoury, he was involving in looking at ways that the urban neighbourhoods next to the centre of Beirut could be revived.

Meker: Founded in 1967 by Nehmé Mehanna, family-run business Meker began by specialising in metal doors and kitchens, before turning its focus to woodwork. Particularly interested in the new needs and lifestyle of Lebanese people, the company created furniture and, in 1998, furniture specifically for schools, while continuing to develop its range of kitchen furniture.

Part 2: From the 90s to the present day

When the civil war (1975-1990) came to an end, the reconstruction of Beirut and a new beginning for Lebanon appeared to be the number one priority when it came to boosting its appeal and attracting investors. Many Lebanese people returned to their homeland at that time. It is against this particular backdrop that design began to win back geographical, economic and creative spaces. Beirut became a creative city, filled with workshops, galleries, schools and architecture offices as well as living environments (bars and restaurants). In the 1990s, the “Hariri-Solidere” plan, which was the result of private initiatives, involved destroying old neighbourhoods in order to open up the views of the sea. The lack of respect for heritage (neither conservation nor restoration) was criticised against this post-war backdrop. On top of that, the large building sites only accelerated the debt that would affect both citizens and businesses.

New geography of a creative city

The specific urban development of the city was not without consequences for creative residents. Urban spaces that were not very close to the centre, in suburbs and wastelands were thus re-qualified and enhanced just by introducing artists, designers and cultural institutions. These examples of urban transformation or gentrification began to happen at an ever increasing pace, mainly due to the total lack of urban planning by the state.

In Beirut, design became a key player in the creative process and, both historically and from a contemporary point of view, was to be regarded as one of the driving forces behind the development of a micro-economy. So it was that at the end of the 1990s and during the first decade of the 2000s, when the Corniche al-Nahr, Quarantine, Gemmayze, Mar Mikhael and Badaro projects were taking shape, and alongside them the development of creative centres, the thirst for design began to re-emerge.

Emergence of specialist galleries and fairs

A number of organisations were set up in the early 2000s and began to imagine, outline and structure a new design landscape. As early as 2002, the XXe siècle gallery offered vintage pieces (from the 1950s to the 1970s) and revealed a whole new aspect of Jean Royère’s career. Joy Mardini and Carwan gallery were committed to introducing the public to what Lebanese design had to offer.

The early 2010s was undoubtedly the high point of the positive energy of design in Lebanon and very quickly, alongside the galleries, a number of fairs were launched, including Beirut Design Week and regionaly Design Days Dubai (2012-2017) offered a new strong visible platform for the Lebanese design scene. In 2017, Beirut Design Fair was the first fair entirely dedicated to design in Beirut.

A Design department within the Académie libanaise des Beaux-Arts (Alba) was created in 2012, thus making it the first school in the Middle East to consider Design as a discipline in its own right. It was Marc Baroud, a recently graduated designer, who taught this subject. The Design department has two main roles: creating new opportunities and becoming a resource for companies seeking innovation.

Featured designers in this section:

Part 3 - Minjara Tripoli

Minjara (carpentry in Arabic), was born out of a desire to preserve the heritage of Lebanese woodwork and bring together traditional craftsmen and contemporary designers in a spirit of innovation.

This project, launched with the help of the European Union, was established to support the wood industry, which was in danger of disappearing in Tripoli due to the sectarian clashes that blighted this region until 2014, which was once known as the cradle of traditional Lebanese furniture and crafts.

Since 2018, it has been housed in a spacious venue designed by the architect Oscar Niemeyer. The building is an iconic example of Lebanon’s architecture, built in the 1960s, and in this space the Minjara project offers a space for creativity, training and synergy. The aim is to bring creative minds together under the umbrella of a label - a guarantee of quality - in order to be recognised both locally and internationally.

After the explosion of 4 August 2020, in solidarity with Beirut, Minjara mobilised local expertise and trained volunteers to make temporary doors to give Beirut residents a minimum level of safety. So the platform also offers direct support for specific projects.

Upholding a real spirit of solidarity, Minjara is both a showcase of Lebanese savoir-faire and a platform for interaction, meeting and research, bringing together different creative minds and constantly encouraging people to reinvent themselves by combining heritage with innovation.

Featured designers in the section:

MAD ARCHITECTURE (Marie-Lyne Daher and Anthony Daher)

BORGI / BASTORMAGI (Nada Borgi and Etienne Bastormagi)

M + A WORKSHOP (Georges Mohasseb and Kareen Asli)

1% ARCHITECTURE (Waldemar Faddoul)

ARCHITECTURE & MECANISMES (Céline Stephan & Tatiana Stephan)

The exhibition (April 24th – August 14th, 2022) is presented at the Centre for Innovation and Design (Grand Hornu, Belgium) in co-production with the mudac and the Fondation Plateforme 10. It will be accompanied by a book that also looks at the various aspects of this fast-developing scene.

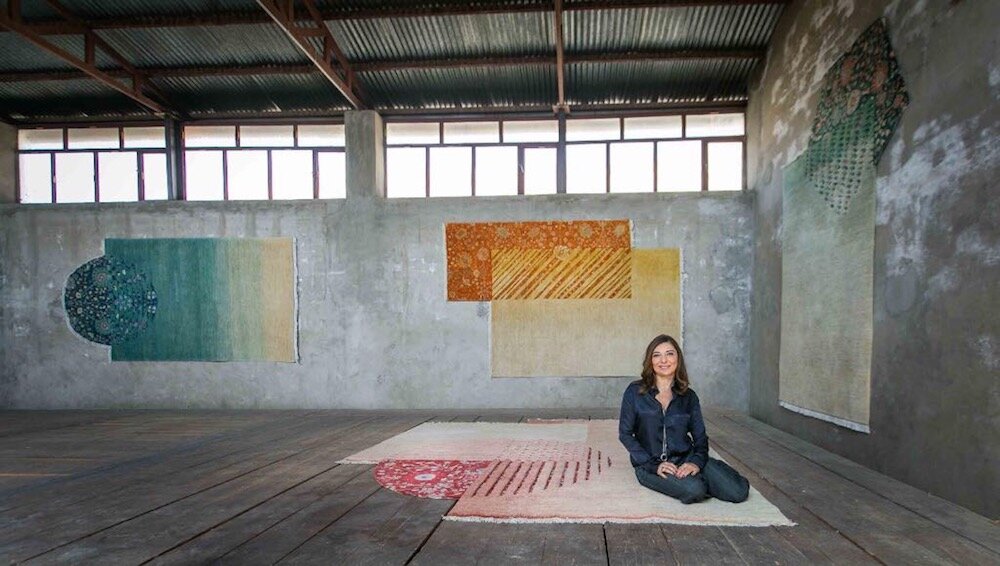

Hero picture: 25kg wall mounted study by 200grs (2014, C Thomas Hage Boutros)

![Un[Mask]Ed By Iwan Maktabi X Collection</a>](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/60e5d1328ba0347d103ca037/1629483099762-G8MGRWVUOLU6D520UOQS/DSC_4995_hero.jpg)